OK. I’ll admit it. I’ve never seen a varroa mite. Just the way it was, with timing of varroa entering the industry, and me leaving it, back in 2000. Just never had the opportunity or particular desire to.

But now, based on an article in the latest NZ Beekeeper magazine, I’ve converted the existing floor to allow for the monitoring of mite drop. The idea is the mites, if they fall onto the floor of a hive, simply return to the hive – I’m not sure if they walk or if they catch a ride with a passing worker bee. But if they fall through a mesh (too small for bees to go through), you can trap them on a piece of core flute plastic. Spreading oil on the core flute makes sure the mites that fall are killed. Then, periodically, you remove the core flute, count the mites, wash it off – and put new oil on it to return to the hive.

This is not a varroa control measure. Or at least not really significant. The idea is to monitor the mite drop levels over time, potentially using it as another measure to alcohol washes, which give a proper sort of “mites per 100 bees” sort of measure.

But for me? Stil never seen a mite? We shall see…

My daughter did the woodwork part, using a lovely piece of macracapa. We were at the DIY Shed in Tauranga, where she has some access to the machinery she needs for her ‘real’ woodworking.

Used the joiner, thicknesser, lovely table saw. Drop saw. A wee bit of bandsaw – and she finished her part of the work, giving me beautiful timber.

Me, I used over-sized screws, drilled too-small pilot holes, forced it when needed, applied a hammer to finish. Glue stains everywhere including a lot of No More Nails since I didn’t cut stuff square, did I? I put it all together while she was at her workshop today so she wouldn’t see what a shoddy, but barely-workable, job that I did.

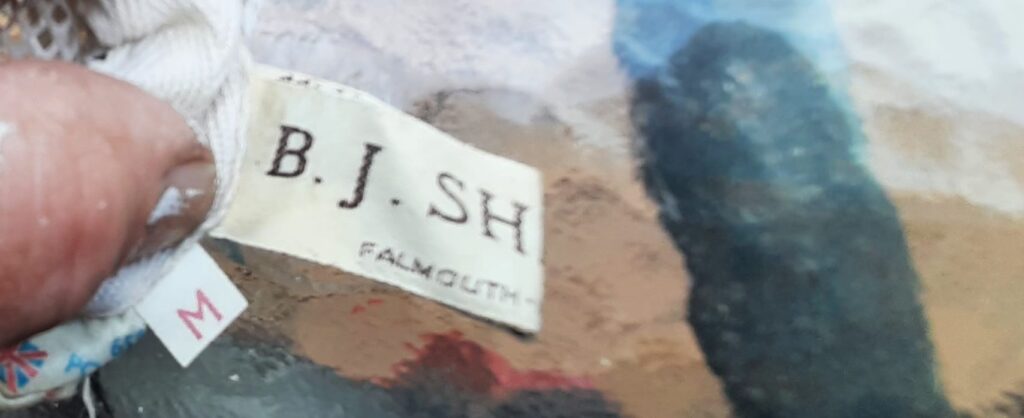

But it is fitted, and the bees have accepted it with no problems. The floor is now reversed, with the original entrance pointing to the back. The new entrance takes the bees in just above the meshed layer. And it should be core flute I’m sliding in the back, but I found a just the right sized piece of glass as a starting point, until I can score some core flute.

Who knows? Might see my first varroa mite tomorrow!